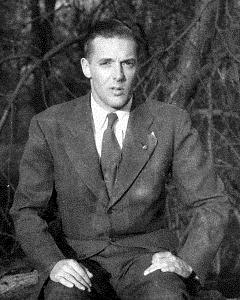

INDIVIDUAL | Inducted 1993 [Now Deceased]

A Chicago resident for more than 50 years, Bruce C. Scott successfully fought federal anti-gay employment policies in groundbreaking lawsuits. In a 1965 decision with far-reaching implications, the U.S. Court of Appeals in Washington, D.C., ruled that a vague charge of “homosexuality” could not disqualify one from federal government jobs. Scott was also and early officer of Mattachine Midwest. Born in 1912, he died in 2001.

Bruce Scott played an important, if seldom recognized, role in the history of the gay civil rights movement at the national level in the pre-Stonewall period. A federal government employee during the Joe McCarthy era, Scott was one of hundreds of gay men who lost their livelihood. But unlike most, he fought the discriminatory practices of the federal government in court, thereby providing the nascent gay movement of the 1960s with one of its earliest successes. His suit paved the way for the 1975 reversal of the federal Civil Service Commission’s exclusion of gays and lesbians. Scott was to the 1960s and civil service employment what Keith Meinhold and Joe Steffan were to the 1990s and military service.

Bruce Scott moved to Chicago in 1922, at the age of ten, with his recently divorced mother. Living on the South Side, he was graduated from Tilden Technical High School, attended Armour Institute of Technology [now known as the Illinois Institute of Technology], and received a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from the University of Chicago. Scott’s first job out of college was with the Corporation Counsel’s office of the City of Chicago. With an interest in government, Scott became a civil servant with the United States Department of Labor and, after serving in the Army in World War II, moved to a new position in the Department in Washington, D.C. He worked for the federal government until 1956, when he was forced to resign under the suspicion that he was homosexual.

When he reapplied to the federal government in the early 1960s, his application was refused on the grounds that he was a homosexual. By this time, Scott had helped found the Mattachine Society of Washington, an early gay rights organization. Mattachine, under the leadership of Frank Kameny, quickly adopted an activist, civil liberties agenda, following the models of the NAACP and ACLU. The group supported a number of test discrimination cases in the courts. Bruce Scott, who served as the group’s Vice-President and Secretary, was the litigant in one of the most significant such cases.

In 1965, the Federal Court of Appeals ruled in Scott vs. Macy that a vague charge of “homosexuality” was not grounds for disqualification from federal employment. The Vector, a San Francisco gay publication, remarked that “a candle has indeed been lighted” for the gay and lesbian community. When the government attempted to present more specific charges against Scott, the Court of Appeals in 1968 again found in his favor. In 1975, having lost a number of similar cases, the Civil Service Commission was forced to suspend its discriminatory exclusion of gays and lesbians. This policy change not only affected thousands of federal employees and contractors, but it set the standard for employment practice throughout the country.

During his protracted litigation, Scott was under a great financial burden because of his inability to work for the federal government. After intermittent periods of unemployment and under-employment, Scott left Washington, moved back to Chicago and began working for the State of Illinois, from which he retired after 20 years of service in 1985. (Note: this entry has not been updated since the time of induction).